About Mr. B's "pseudo-apology" in his latest column, claiming that 'to make no mistakes is the same as to not do anything', one can reply, 'make lots of mistakes -- that means you did a lot'.This excuse is still commonly used, and the reply is still apt.

Saturday, September 19, 2009

Mistakes

From Eliyahu Fasher's personal archives, a quote in a letter to him. The letter, from 1967, is a note by chess problemist A complaining to Fasher about chess columnist B:

Saturday, September 12, 2009

God Knows what the Mailman Made of it

A postcard from a fellow-problemist to Eliyahu Fasher, 1967. Image credit: Yad Tabenkin institute, Eliyahu Fasher's archives.

Chess jargon -- and problemist's jargon in particular -- is notoriously odd-looking for the non-initiated. Hans Ree notes in his article 'Sic' (The Human Comedy of Chess: A Grandmaster's Chronicles, 1999, pp. 284-285 [Milford: Russell Enterprises]):

"Do you people really talk about 'problem composers'?" my interlocutor asked with amazement. "Certainly, that is the usual term," I said. She was silent for a moment, and then she smiled and said: "That is the term I have always been looking for, for my husband."Here we have another example. 'You asked without [picture of black knight], so without [picture of red rook] f6'. What are those weird pictures? And what is f6 -- in Hebrew, written like 'and 6' ? 'And 6' what? No doubt some code. What's more, the letter says that in the previous form there were 'four threats', but now the writer is only giving 'two threats'.

A threatening letter in code. Who sends something like that in a postcard, anyway, which anybody can read? Should I, the mailman, report it to the police?

P.S.

I apologize for the wonky formatting in the last two posts -- blogger's formatting is acting up again.

A Good Reason for Speeding

Saturday, September 5, 2009

Andrew McMillan's Investigation of the Alekhine "Checka" Arrest Affair

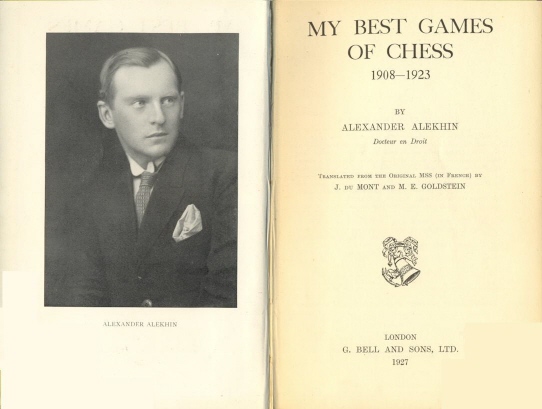

Alexander Alekhine. My Best Games of Chess 1908-1923 (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1927). Photo credit: Edward Winter's Chess Notes #4310.

One of the well-known stories about Alekhine is that he was nearly shot by Odessa's secret police in 1919, only to be saved by Yakov Vilner's intervention with the Ukrainian chief commisar, Kristian Rakovsky, due to recognition of his chess genius. Vilner worked in the Odessa military tribunal at the time, and told Fedor Bohatrichuk this story in great detail, which Bohatrichuk quotes in his writing (in pages 51-52 of his book Moi' zhiznennyi' put' k Vlasovu i Prazhskomu manifestu [My Life's Path to Vlasov and the Prague Manifesto], Globus Publishing House, San-Francisco, 1978.) Andrew McMillan generously sent me both Bohatirchuk's original Russian writing and a translation into English.

Different versions of the story exist, apart from the one above. Andrew McMillan also informed me (my additions in brackets for clarification):

In his [Russian-language] well-researched book on Alekhine, [Alexander Alekhine, 1992, Moscow] Shaburov states that the story of Alekhine being arrested by the Odessa Cheka in April 1919 and rescued due to his chess reputation first appeared in CHESS magazine in its Dec. 1937 issue. In that story Trotsky himself is involved. Shaburov established from a number of sources that Trotsky was not in Odessa during this period. Shaburov then mentions the version of this story in Müller and Pawelczak's book about Alekhine . Shaburov also briefly gives Bohatirchuk' version that Vilner told him that he saved Alekhine by getting Rakovsky to intervene. Shaburov acknowledges a different version...A summary of both Bohatrichuk's 'Rakovsky' version and of the 'Manuilsky' version can be found online, e.g., at this link. McMillan notes that Shaburov's research is thorough and his email is merely a brief summary, and also that -- unsurprisingly -- Shaburov found little original documentary evidence. Shaburov (says McMillan) further notes in his book that a similar story was told about Ossip Bernstein in Edward Lasker's obituary of him in the April 1963 Chess Review, pp. 104-105 (which McMillan also scanned and sent to me) and elsewhere. Shaburov, notes McMillan, speculates that since Bernstein and Alekhine were both in Odessa at the time, somehow what happened to Bernstein was told of Alekhine.that Agriculture Commissar Dmitry Manuilsky was the one who intervened.

However, it seems to me the opposite is more likely. Bohatirchuk's recollection of his conversation with Vilner is full of specific details (in his original writing, if not in the summary posted here and in the link above) -- names, dates, etc. -- while Lasker's claim about Bernstein's has very few verifiable details, and tries to "make up" for lack of verifiable evidence with a dramatic story.

Lasker does not mention who saved Alekhine's life, but only that it was 'a superior officer' who overruled the execution order of 'one of those sadistic minor officials'. It has the chess master prove his identity by playing a game (literally for his life) with the officer, 'winning in short order'. In Lakser's version, the master was not only under sentence of death, but already lined up against the wall in front of a firing squad (!), together with many others, when the 'superior officer' discovered his identity -- and those others' lives were also saved by the master when his identity was confirmed by winning the chess game with the officer. Finally, Bohatirchuk unquestionably was in revolutionary Russia (or the Ukraine) at the time of this alleged incident, while Lasker, of course, was not.

Is it not more likely, on literary grounds at least, that if anybody was in fact arrested and threatened with execution, it was Alekhine, and that story 'grew with the telling' and was transferred to Bernstein?

Above all, there is Alekhine's own cryptic handwritten note, forwarded to me by McMillan, confirming that he was in fact imprisoned -- and released -- by the Checka (or Tsche-Ka). As McMillan notes:

So far all I can send you from these is the unpublished handwritten note Alekhine included in the original manuscript of his book Das Schachleben in Sowjet-Rußland Berlin 1921. It confirms that he was imprisoned by the Odessa Cheka but does not provide information about the reason of his imprisonment or release. Buschke reproduced the note in the Sunday, August 5th, 1951 issue of Chess Life, page 3.The note -- in German, translated by Buschke into English -- is reproduced below:

תוויות:

Alekhine,

Bernstein,

Bohatirchuk

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)